I’ve been gone a long time, and now that I’m back, one of the first things I’m doing is touching base in old familiar Buddhist places where I’ve hung out in the distant past. In science fiction fandom the word for what I’m doing is called “ego-scanning”. I type “Blanchard” into the search box on a forum and see if anyone’s read anything I’ve written. Professor Gombrich said it takes about ten years for anyone to take notice, so it’s time now, right? And there have been a rare few mentions.

What I like about ego-scanning is that it turns up interesting on-going conversations about subjects I’m keenly interested in, and while doing this over on Dhamma Wheel, I encountered several mentions of a paper on dependent arising (“DA”) by someone named Bucknell. It turns out I have had this paper on my computer for a long while, along with hundreds of others by a wide variety of scholars, researchers, and opinionators, but like most of the hundreds, I’ve never read it.

Bucknell’s Investigation

Roderick Bucknell’s 1999 paper “Conditioned Arising Evolves: Variation and Change in Textual Accounts of the Paṭicca Samuppāda Doctrine” got praise from DW participants, but in reading it, I found myself sad that it was written before Jurewicz’s paper in the 2000 Journal of the Pali Text Society, which might have helped explain some of the puzzles Bucknell was trying to solve. In particular, the problem of the apparently non-linear definition of viññāṇa (traditionally: “consciousness”) when it’s used in definitions of phassa (“contact”), out of sequence of the usually orderly-appearing dependent arising.

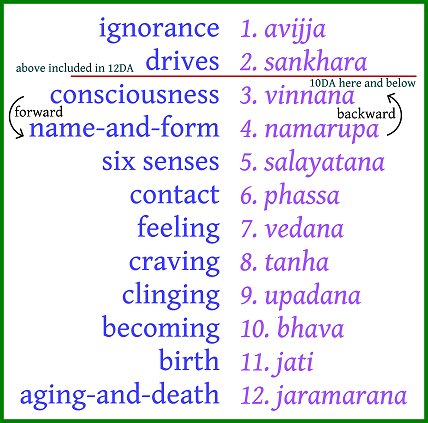

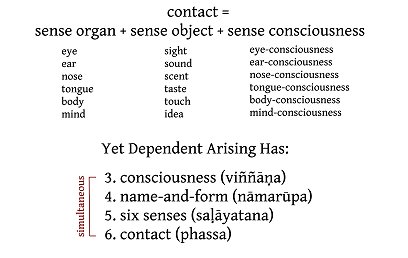

Working primarily with the ten-link DA, he was attempting to sort out what the earliest version was, or if there was an eo-DA that the versions we have evolved from. He seems to have decided that the definition of contact as having three components that come together — a sense organ, an object for that organ, and a particular consciousness that recognizes the connection, resulting in six types of consciousness1 — is a clue because it pulls consciousness into action simultaneously with contact,2 when there are links between them. On the face of it, when expecting that DA describes a linear series of events, from start to finish, it makes little sense that links a distance apart are combined in one moment’s experience. It’s understandable that he’d try to use that as a lever to pry DA apart to discover clues to its evolution.

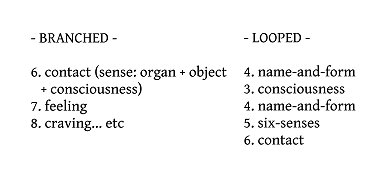

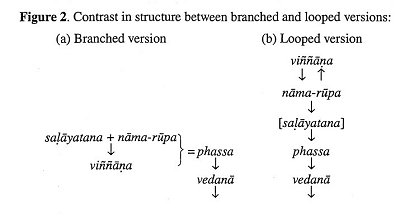

He begins by working with a theory that there could be a “branched” DA that has the three-item “contact” at the start, in which consciousness and name-and-form are not interdependently looped — in fact nāmarūpa isn’t even present anymore,3 and consciousness appears only within the definition of contact. The other possible candidate he comes up with is a looped version in which consciousness and name-and-form are interdependent and at the beginning of the chain, and the three-item contact is not a part of it. In the middle of the paper, he says that there are two possibilities:

(a) The two versions accurately represent two distinct teachings imparted by the Buddha, which happen to have much in common.

(b) The two versions represent a single teaching imparted by the Buddha, the present differences between them being due to faulty transmission of the tradition.

It’s probably not surprising that I disagree with him, first, on their being just two possibilities to consider, and second, on either of those being The Answer to the questions of early forms of DA. There is a third possibility, in which option (b) is half right: there are two versions here that represent one teaching, but that’s not because of faulty transmission. It’s because they are two different views of the same lesson — so almost what’s suggested in (a): two distinctly different teachings but actually on the same subject, so it’s not happenstance that they have much in common. They are perfectly compatible in that they are discussions of the same version of DA. This is because the definition of contact as having three components is looking at the makeup of that one component of the chain of events, looking at it through a higher power lens, and from a particular, apparently unexpected, angle.

Two Points

To understand this, two points about dependent arising in its fuller formulas need to be understood.

The first is that the full chains (whether nine, ten, eleven, or twelve links) can most easily be understood as having three parts. (Part 1: The Drives) From the beginning up to the six senses if the senses appear, otherwise up to name-and-form — this is an overview of what drives the whole process being described. (Part 2: The Rituals) The action, from contact through, perhaps, becoming (you can throw becoming into part three if you like; I won’t argue). (Part 3: The Results) From birth to aging-and-death.

The second point requires a good understanding of the first, especially the way that the earliest set of links are not so much actions as forces that apply. What that means, when looking at DA is that the two basic directions — beginning to end, or end back to the beginning — represent two almost entirely different definitions in many links. Going forward they’re in a category I’ve found no word for because they begin with drives (which we moderns think of as “real” and “active”) which, to the point of view of the Vedic world, are not real. They’re more like “potentials” — like their view of fire as existing even when it’s not burning in the world, or like the divine: influencing but not visible, not yet manifesting in the world.

That’s the forward-looking view. The backward-looking view is quite different because things “got real”, as I’ll explain below.

In this post, when I speak about the directions, forward or back, I am speaking only of dependent arising, emphasis on the arising. Forward: “from this, that arises”. Backward: “this arose from that”. Note that the action is in the same direction, but there is a difference in tense in the way it’s expressed as “arising” in English: present implying future action in the forward direction, definitely all past tense in the backward. Please keep clear in your mind that when speaking of “backward” it’s not cessation we’re talking about here, only arising. Arising in both directions.

The Buddha Thought Backward, Then Forward

It’s my perception that the Buddha discovered what’s going on by looking at the end result4 — dukkha (“suffering”) — and asking what its cause is. Using aging and death as a stand-in for dukkha, the answer is “Birth is the cause of aging and death”. “This” (death) arose from “that” (birth).

When working DA backwards, looking at the final effect first, to his point of view, every link in the chain was inevitable and unavoidable. We know this is true because dukkha happened. So when looking back, there is effectively no “If I’d done things differently” possible because what’s done is done. (I believe this is what he’s expressing with part of his post-liberation declaration re: “…what had to be done has been done.” Of course it has or you would not know you were liberated, right? What needed to be done to get there has been done.)5

So when he’s talking about any part of the chain of conditions being the basis for an effect to arise, working backward, it’s done and dusted. The conclusion is foregone, absolutely. All the previous links are, in a sense, included in the final result because they already happened.

In the other direction, from the beginning to the end, there is still the possibility for the chain to be broken. This is true whether we’re looking at the large scale (theory) or small scale (i.e. an example).

Let’s say we’ve experienced a bit of dukkha, and we use DA to work it backward, and we can clearly see in a real-life way every link having happened. We can examine specific moments that are examples of the general principles in each link. We can’t change those specific events, sure, but if in imagination we take those events and imagine it starts happening again, we can see how, starting at the beginning and working forward, if we change one thing here or there, it affects the rest of the chain and the result would be different this time. As our imagination moves forward we may come up with a specific chain of events that would be our idealized version, but if we are realistic we know things aren’t likely to work out exactly as we imagine them, but we can be pretty sure events would be different from the way they turned out, probably better. The possibility for change has to always be there — in the future — or there is no room for liberation from dukkha.

Maybe we add just a little bit of knowledge at the beginning, which affects what happens afterward: the driving forces are still having an effect, but we can see it. At the earliest point the Buddha says we can see it — which is at “contact” — and think about affecting the outcome we do see it. Feeling born of contact still arises, but we’re more aware of why we react the way we do, of the forces having an effect on our interpretation of events, affecting how we feel about them and how we react. The result can be different because the dash of knowledge gives us the option to refuse to be driven to dukkha-inducing behavior from that point on. It’s using that sort of effort of thought that gives us insight into how dukkha happens in our lives, and how we can break the chain in the future. This is where the power of the lesson of DA lies, in the insight, and the freedom it gives us to behave differently, consciously.

The Buddha talks very directly, in various suttas,6 about how to break the chain as early as possible. He focuses on the way contact will generate feeling, but he seems to recommend that we stop to see what’s going on at that point. This is why contact is so important, and its frequent appearance is likely why Bucknell noticed it and began thinking of it as an alternative chain. It is the point where what’s happening in dependent arising becomes “visible” — felt, actually: noticeable, real. Prior to that, moving forward, it’s all unmanifested drives. But those forces still have an important part to play to make that felt-contact happen.

What Direction Are We Going In?

What has made it difficult to understand how the definition of contact fits with the usual descriptions of DA, is that the two directions are different, but that’s not obvious. In defining contact (phassa) as including something earlier in the chain — particularly an example of “consciousness” (viññāṇa) — we’re looking at contact as already having happened. The definition effectively tells us it has already happened by including — as Bucknell comes to see in his paper — the three links just prior to contact: the six sense organs (saḷāyatana), their objects (via nāmarūpa),7 and the matching sense-consciousness (via viññāṇa). But somehow, despite having recognized that contact includes the three links just prior, he has missed this clue that we’re looking back.8 Part of the problem may be that he reordered the links, so he obscured the way the Buddha always names the elements of contact — sense organ, its object, its consciousness — in exact reverse order of the links Bucknell recognized as appearing in the standard version of DA– saḷāyatana, nāmarūpa, viññāṇa. His Branched version, with its revised order, is shown in Figure 2 from his paper:

Bucknell has moved the six senses and name-and-form before consciousness9 but the Buddha also says that the three together make for contact. The Buddha says this, and orders it the way he did — in exact reverse order — for good reasons, one of which is, no doubt, so that we’ll recognize that the definition of contact is made up of its three preceding links, in their order. From that we’ll know it’s looking at contact having happened, driven by what came before.

With his description of viññāṇa as eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, etc., the Buddha was clear in saying that viññāṇa represented awareness of contact with the six sense objects. Why, then, did he not specifically say that the six sense organs fell under saḷāyatana, and the six corresponding sense objects were under nāmarūpa? It’s impossible to know what all his reasons were, but it may be in part because nāmarūpa and saḷāyatana are larger categories that include not only their six sense matters when we’re looking backward at them as done and dusted, but their definitions are very different when looked at going forward, considering possibilities.

There are differences to all three in the two directions. The difference in direction is why we only see viññāṇa associated with sense-consciousness when looking backwards from the definition of contact.10 Through the detailed view of contact we get to see how, when looked back at, nāmarūpa is a real condition for viññāṇa, not in that moment an unseen force, but made real by events. A specific experience of sense-consciousness does not arise unless nāmarūpa has gotten sense-data from a sense organ (via saḷāyatana) and then provided its understanding of that sense-object to consciousness, which then lights up with an awareness — probably full of pre-conceived ideas about the object — of what touched that sense.11 The six senses, moving backward, are the sense organs in action, making contact. In the forward direction, as a drive, they are as-yet unfulfilled, driven by all that came before to go seeking information, not yet made real, by contact.

The backward look at name-and-form feeding consciousness is, for Bucknell, one half of the problematic “looped version” shown on the right above. Four suttas tell us that viññāṇa and nāmarūpa depend on each other. Unaccountably for many studying dependent arising, two of those four describe not only the loop but also make reference to the full standard version which Bucknell — and I too — believe implies the three-fold definition of contact. He sees the two versions as incompatible and their appearance together in the same sutta as being in need of a solution because the branched version has such a different order, and different descriptions than the looped. I see them as compatible and easily explained because they are simply examining DA in different directions that represent (forward) unrealized drives vs (backwards) realized past events.

The other half of this perceived problem is that in the suttas the relationship between the two links going in the other direction, forward, with consciousness a condition for the arising of name-and-form, has a completely different description. That relationship is described with reference to consciousness landing in the mother’s womb, and an individual with an identity (name) -and- body (form) being generated, the two depending on each other. We’ll deal with why that is in the next post.

We Have/Had Contact

Contact has to be defined by the moment it is happening, or when it has happened, because before that it didn’t exist. Whether you look at contact forward or looking backward, to exist at all the previous links have to have happened also.

The definition of contact as including a sense organ, its target, and its consciousness seems to be quite early, given how often it appears. In a search of suttas (that I’ll describe below) I found the Pali word cakkhuviññāṇa (“eye-consciousness”) — the most common of the “consciousness” words used in descriptions of the threefold components of contact — appeared 132 times in DN, MN, SN and AN suttas,12 the majority of them in the same paragraph as phassa. I am speculating that the three-fold definition came about before the first two links in the twelve-link chain were added, so that may be why they are not overtly included. Or it may just be because they aren’t required to define contact in a way that almost anyone should be able to understand; the earlier links would just add confusion.

What we have in the definition is that contact is seen as having already happened, and at the point it happened, a sense organ was, of course, involved — that comes from saḷāyatana, the senses, which is link five. Awareness was involved — that’s viññāṇa, usually translated as “consciousness”, link three. And of course an object for the sense to contact is involved — that comes from nāmarūpa, name-and-form, link four, where it can be an idea (from nāma) if the “mind as a sense organ” is the one activated, or an actual form (from rūpa) that generates touch, taste, scent, sound, or sight, something physical made up of the elements. Three pieces, in order, that immediately precede contact are described as needed for contact to have happened.

When we understand that that’s what’s going on — contact is defined as having happened, pulling the earlier viññāṇa (and the others) into its definition — it makes perfect sense. And it in no way conflicts with the normal chain of dependent arising when all that the three-fold definition of contact describes is the most important bits of the driving forces, the three immediately preceding the event of contact, being named as required for contact to happen. It’s just a magnified look at contact and what went into making contact happen. Simple.

Bucknell overcomplicates it by mistaking contact’s definition and the way it is often followed by the links of DA that come after it for a lesson intended as complete rendering of DA. This despite the fact that early in his paper he has recognized — and I do, too — that the Buddha often uses limited links to focus on just the part of the lesson he’s talking about at that time. In these lessons the Buddha was focusing just on the part of DA that is the most readily visible.

Check Please!

To see if my understanding could be correct, I did the search for cakkhuviññāṇa, mentioned above, to try to locate as many of the definitions of viññāṇa via the senses as possible, so that I could look to see if there were any instances of that sense-based consciousness moving in a forward direction, causing the arising of name-and-form — or does nāmarūpa only arise from a generalized naming of consciousness, or from the unusual description of a literal birth? If I am right that contact is being defined by its moment of having happened, then nowhere should cakkhuviññāṇa as eye-consciousness be described as a condition for name-and-form to arise. None of the six sense-based instances of viññāṇa should be described as conditions making name-and-form arise. I did a search on phassa (2.7k appearances) and looked for cakkhuviññāṇa to appear in the same paragraph — which it did, over 100 times. And in those hundred appearances of cakkhuviññāṇa I found only two suttas in which nāmarūpa appears in the same paragraph with cakkhuviññāṇa. They are in SN 22.56 and SN 22.57.

The two suttas parallel each other, in that they go through each of the five khandhas (components of our identities, “aggregates”): form (rūpa), feeling (vedanā), drives (saṅkhārā), perception (sañña) and consciousness (viññāṇa) while twice describing their origination and cessation in line with dependent arising. The exceptions are that form depends on nutriment, and perception and drives on contact.

Because they are presented in the usual order for the khandhas, and because some use DA definitions of their origins, at first it looked to me like I’d found evidence that I was mistaken. Consciousness is described as arising from name-and-form, as in DA which means it’s here part of the looped version that Bucknell, in his paper, saw as conflicting with the definition of contact — contact that includes consciousness as six-fold via the senses. Yet in these two suttas consciousness is defined — simultaneously with “the loop” — as being that six-fold variety.

This seemed puzzling, and sure seemed like Bucknell’s full-on option (b) — a corrupted combination of the two: branched and looped.

But no, it’s not. This appearance of conflict is also explained by contact seen as having happened. It’s also supported by the full rendering in these two suttas of viññāṇa and the rest via the Four Noble Truth’s lens. In the translation by Thanissaro:

And what is consciousness? These six classes of consciousness — eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, nose-consciousness, tongue-consciousness, body-consciousness, intellect-consciousness: this is called consciousness. From the origination of name-&-form comes the origination of consciousness. From the cessation of name-&-form comes the cessation of consciousness.13 And just this noble eightfold path is the path of practice leading to the cessation of consciousness, i.e., right view, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.

The Buddha is discussing his knowledge and understanding of each of the five aggregates, using the formula used in the Four Noble Truths: what it is, its origin, its cessation, and the way to its cessation (this last in every case, the Eightfold Path). Because he’s speaking of knowing these things, he is looking back at each of them, describing past experiences with them.

He even defines saṅkhārā in terms of each of the senses, as arising from contact, clearly indicating a backward look, describing that driving force made manifest, activated, real. He also says of that six-fold sense-based saṅkhārā: “This is called saṅkhārā.” But we know saṅkhārā well enough to know that far more than saṅkhārā-as-sense-based is included within its scope. He isn’t saying saṅkhārā’s definition is limited to its sense-based appearance, rather he’s saying that the sense-based forms of saṅkhārā are included within the definition of saṅkhārā.

The same pattern is then true of the above discussion of consciousness. While it’s tempting to think that “this is called consciousness” means whenever we see viññāṇa it is referring to the sense-based versions, it’s the other way around. The sense-based versions of consciousness are included in the definition of viññāṇa but viññāṇa isn’t limited to sense-based versions. In this quote, they are part of the review of things that have happened. When moving forward, seen only in imagination, viññāṇa is defined differently.

While consciousness is said to arise from name-and-form (indicating the loop), name-and-form is not said to arise from instances of sense-consciousness (which would indicate the branch). Nowhere in these two suttas does it say that this six-fold consciousness is a condition for the arising of name-and-form. We are here looking at the backward-looking, “it’s all already happened” direction of events in dependent arising. From where we stand, still smarting from our experience of dukkha, we can see how consciousness arose from name-and-form. It was an individual instance — a sense-conscious instant — that arose from name-and-form which contained an object for that sense. It also arose from one of the senses contained in the still-earlier saḷāyatana. That instance of sense-consciousness happened — boom! — when all three bits occurred simultaneously.

These two suttas, then, despite having sense-consciousness and name-and-form together in a paragraph, don’t describe sense-consciousness as a condition for name-and-form. As far as I have seen, there is no sutta in which the six-fold description of consciousness is said to be a condition for the arising of name-and-form. If you spot one, I hope you’ll comment below and cite it so I can have a look. I’m willing to be shown I’m mistaken.

Bucknell’s instinct to move saḷāyatana (the senses) and nāmarūpa (containing the objects of the senses) before consciousness is understandable, but it only confused matters. From then on he was pretty much lost, inventing theories about monks trying to make things more uniform, them rearranging things in the wrong order, later monastics trying to fix things by supposedly being the ones redefining consciousness and name-and-form in terms of rebirth, making it all worse — a very ornate tangle with, as Bucknell admits, no supporting evidence.14 The view I offer of DA is much simpler and works with what’s visible in the suttas. It’s an example of what I described in my earlier post on approaches: putting a reasonable amount of trust in the transmission of the suttas and thinking in terms of “how can this be understood as correct” rather than assuming that our confusion happens because what we’re reading is all screwed up by later generations’ meddling.

The Other Viññāṇa

There is a reason all the above seems so clear to me. That’s because I’m seeing dependent arising as having a structure that’s shaped by the Vedic view of the world starting with the creation myth in those first five links. This has made it very clear to me that Part 1 (The Drives), when moving forward, is not active but passive: it describes what drives the rest. However, when seen in reverse those same words represent active forces that did play a part, so while viññāṇa going backwards from contact describes a consciousness that was, at that brief moment, aware and paying attention to something that was happening that did result in dukkha, when described going forwards, it is a silent seeker of information acting as a force applied to push name-and-form to find what consciousness is hungry for.

In the Vedic literature, hunger and its satisfaction plays a big part. It is hunger for existence that drives the cosmos and the ātman to come into being. Alone, subject with no object, unable to see itself to determine if it exists or not, it has to create a second self with senses to satisfy that hunger. The second self provides the subject with an object to look back at itself, to whisper apparent truths to the subject about its self.

Consciousness on the moving-forward side represents that hungry, seeking, “not yet real to itself” ātman. It is positively driven to seek information through name-and-form — name-and-form which also represents that second self that will feed consciousness what it needs. In the moment of contact, for just that moment, consciousness is satisfied, but a second later it needs to be fed again (insecure little thing, isn’t it). It always wants more information to support its growing understanding of itself and its place in the world. Think of it this way: it’s not real except in the moments when name-and-form is in the act of feeding it information gained, so naturally it turns back there and sends name-and-form back out to seek more soul-satisfying feedback.

Consciousness drives name-and-form to seek, name-and-form comes back and feeds consciousness what it has found.

This is why viññāṇa gets a different definition when dependent arising is moving forward. It’s not the briefly satisfied, “made real for a moment” six-fold, sense-based, actively aware consciousness. It’s the hungry, unsatisfied, driven version waiting for its second self to show it something.

It is because the whole of Part 1 — the set of links representing the drives — is based on a creation myth that’s based on human procreation, that consciousness often gets described via conception (“descent into the womb”) and name-and-form gets described via birth and the shaping of a human through childhood to maturity. With the context lost, those two very different descriptions seem like conflicting information, all out of sequence. No wonder we’ve been confused.

Why does the Buddha talk about procreation instead of the myth? I imagine it’s because he’s trying to get people — even those not students of the myth and rituals — to see a pattern of events that’s going on in our minds by using real-world models everyone is familiar with. This is the way teachers before him called to mind new concepts, and it’s what he does as well.15 Students of the myth would come to recognize the unstated model of procreation, conception, and birth as linked to the myth. The myth and the rituals drawn from it provide an even stronger model to break through to the insight the Buddha is pointing out for those familiar with them.

Clearing Up A Few Points of Confusion

One last very important observation after seeing all the above, one that addresses some confusion about “consciousness” and — by extension– the rest of the links.

Up above in the quotation from SN 22.56, there’s this phrase: “From the cessation of name-&-form comes the cessation of consciousness”. I have seen lots of concern and misunderstandings about the need for consciousness to cease. It’s one of those points used to argue that the Buddha is saying we can only be truly free of dukkha after we have died post-liberation. But it’s worth noting that what we’re seeing here is the Buddha being specific in saying that name-and-form has to cease to stop consciousness, so he’s working backwards. The consciousness he feels that needs to cease is the one that inevitably led to dukkha. It is not all forms of consciousness he is describing as needing to cease, it’s just those incidences of awareness that will, by the end of the cycle, be seen to have caused us the sorts of suffering that is avoidable if we wise up. If I recall correctly, the Buddha doesn’t limit his mentions of the cessation of consciousness only in backward-moving discussions, but he shouldn’t need to be this clear every time. If we understand that what’s being discussed in DA is a theory describing what leads to dukkha, and only what leads to dukkha — it doesn’t include anything that doesn’t lead to the kind of suffering that we can see for ourselves in this very life, and free ourselves from in this life — then we don’t need to be told he’s telling us that dukkha-leading consciousness is what needs to stop, not all the other examples of consciousness that don’t lead there.

By extension, this is true of every link in DA that we get told needs to cease. In every case they are effectively defined as events, moments, actions, and thinking that lead to dukkha. Nothing that doesn’t lead to dukkha is part of dependent arising. Just as not all consciousness needs to be stopped, neither does all contact, all feeling, all birth, etc.

Bucknell’s Mysteries Solved

We’ve seen that the apparent conflict between the “looped version” of dependent arising and Bucknell’s “branched version” that starts with contact made up of three items (which he and I agree are the three links traditionally listed just before contact) is resolved by recognizing that the definition of contact is backward-looking. The lesson on contact then moves forward to show contact’s possible effects on our behavior. In fact, both the looped and branched versions describe events with a brief look backward — in the case of the loop, it’s nāmarūpa‘s sense-objects becoming the focus of viññāṇa‘s attention, then viññāṇa drives nāmarūpa onward (in what ways? see the next post). There is no need for the convolutions he describes of confused monks changing things around and messing it all up — events we have no evidence for — when the logic of the suttas themselves are seen for what they are. Bucknell recognized that the direction DA takes, forward or backward-looking, had an effect on what was described and how it was described, but missed how different the two directions were and how much they affected definitions.

Bucknell mentions a few smaller conundrums in his paper that I don’t find his theory explaining, though I can explain them. One is why the Buddha used the potentially confusing term nāmarūpa in the first place — which I’ll cover in the next post.

Another example of a question he asks that needs an answer is when he says that “there are discrepancies arising out of the place of nāma-rūpa” in dependent arising. He specifically cites contact and feeling being defined as included in name-and-form. That one has, I think, two answers. Contact is easy, because nāmarūpa doesn’t provide its backward loop unless activated as part of contact, so we can see that contact is included when it’s the active form of nāmarūpa, looked back at it. What it’s telling us, I believe, with including feeling (and other qualities, like perception) is that name-and-form is where memory resides, where we accumulate definitions of things, the way we categorize them. Nāmarūpa is giving consciousness its understanding of what it has come into contact with. Whether it is contact with an idea, or with sense-information about a physical object, it’s passing on “feels good” “feels bad” or “meh, not interesting”, along with any deeper added perceptions via taṇhā and upādāna.

Another question that Bucknell seems to leave hanging is one about how consciousness can be a condition for sense-objects. His question seems to be, “If viññāṇa conditions nāmarūpa, and nāmarūpa contains sense objects, how would it be the case that consciousness is a condition for the arising of objects”? He calls this question “transparent and counterintuitive”. I’m not sure how it’s transparent but it is certainly counterintuitive because it is, as the Buddha is known to tell questioners, an incorrect question: it’s based on a misunderstanding. The definition of nāmarūpa‘s function of representing sense-objects is backward-looking; it’s what it feeds consciousness. Sense objects are not part of the forward-moving name-and-form. Consciousness is driving a different aspect of nāmarūpa, as driven to seek information, and as itself a drive that pushes the senses.

The City

Finally, there’s the sutta “The City” which Bucknell makes reference to in a couple of places in his paper, as an example of points of confusion, given that it mentions both the loop and also cites a standard version of DA. In noting that sometimes the looped version says that DA turns back and “cannot be traced further back than nāmarūpa — this despite the existence (sometimes in the very same sutra) of the standard version” he implies that this happens more than once, but it only occurs in “The City.16

I understand that having the Buddha mention the two versions in the same sutta is confusing, but as I explained in my paper on it, the solution is actually quite simple. This time it has nothing to do with forward or backward-looking views of DA, but has a lot to do with how we approach the suttas, whether as probably corrupted (as Bucknell and others do), or as somehow logical. In the case of “The City” my nature as a story-teller and lover of others’ stories makes what’s going on so clear it’s startling. The frame for the piece is the Buddha telling us about how he came to his awakening insight into dependent arising as being like someone who followed an overgrown path through the jungle to a city buried in vines and filled with undergrowth, who then goes on to restore the city to its former glory — the implication being that what’s described in dependent arising has always been there, has been known before, and is simply being independently rediscovered by the Buddha.

In this sutta he considers the problem of our experience of dukkha “headed by aging-and-death”.17 From aging-and-death he works backward — an example of one of the suttas in which he tells us his initial insight was worked from the last link of DA looking backwards.18 The Buddha ends his backward rendering of this early version with the interdependence of name-and-form and consciousness, and then does indeed say it turns back there and goes no further — this still in his description of his earliest insight. We then return to the frame story, in the Buddha’s later-in-life “present” in which he ends with his direct experience, direct knowledge of eleven links, back to saṅkhārā — so a description of the twelve-link “standard version” leaving out only ignorance which, logically, is left out of his naming of links he directly knew because it is a negative state, which isn’t correctly described as “known”. He has told us, in “The City” that his early “discovery” of DA was the one with ten links that he described as stopping and turning back at viññāṇa, and that later in life he described it as going further. There is no conflict here, and no confusion necessary if we simply recognize the Buddha as telling us a story of his past.

Viññāṇa Summarized

Viññāṇa has two different definitions and purposes in its place within dependent arising.

In the forward-looking rendering of DA that describes a theory about how dukkha is produced, it is one of the driving forces that pushes us to create a sense of self: of who we are and of our place in the world. It’s this building up of beliefs about how selves fit into the world that the Buddha was trying to point out as leading to trouble. In the first set of links, he used the creation myths of his time, which were models for (or modelled on) beliefs about procreation, a structure sure to be familiar to most of his audience. The craving for existence brings about conception, birth into a new identity, and senses ready to learn about the world. This is the general order of the initial links, with viññāṇa representing conception and the development of the fetus as well as eventual mental processing power as a youth and adult. In a couple of suttas, the Buddha used those very concepts to describe the relationship between viññāṇa and its “looping” partner, nāmarūpa: conception, birth, growing up.

The concept of a “self” descending into the womb, growing, coming to birth, and developing was also used as the basis for familiar rituals — saṅkhārās — in his culture. These saṅkhārā rituals were a sort of second birth believed to improve the self, leading to a better life and rebirth, so in using rituals modelled on craving for existence and development of the self, the Buddha was pointing out that a similar process was happening in the mind: the self he was speaking of didn’t descend into the womb but was instead created through a parallel set of rituals we perform in our own minds, habits of thinking that created our sense of self, a sort of second self. Perhaps we can see that self we build as second to our Buddha Nature. The self we build is perceived as separate, and as such obscures the nature we are born with, as not separate.

In the forward-looking action of dependent arising viññāṇa is a parallel for the hungry driving force that, in the Vedic world-view, created the universe as well as creating the rituals that hold the universe together and improve it, at the same time improving individuals. Moving forward, viññāṇa is a consciousness hungry for information about itself and the world, out of which it builds its belief systems about itself, others, and the world.

In the backward-looking view of dependent arising, viññāṇa is no longer just a drive, but is an example of that drive fulfilled. It is always described as having been activated by a moment of consciousness of an event that begins with a sense. The possibilities of examples of sense consciousness include any of the five physical senses but it seems the Buddha is primarily pointing out contact with the mind: ideas coming from others (social forces) as well as ideas forming in our own minds resulting from our experiences.

Much confusion results from failing to recognize that the two directions discussed when considering dependent arising are very different: one describing how events often do go, the other describing how they did go.

Dependent Arising: The Earliest Rendering and Meaning

Dependent Arising, as a teaching, undoubtedly evolved over the course of the forty-odd years of the Buddha’s teaching career. When he tells us in “The City” that he originally included only ten links, I believe him, though it’s my honest expectation that the representative terms he used for each link, and the formatting was unlikely to have initially been what we see in the perfected versions. I’m in favor of believing it started out more like the one revealed in “Quarrels and Disputes” — different language, a more clearly dual “inside/outside” format — but in its deepest essence effectively the same lesson. Rather than monastics misunderstanding and messing it up, my perception is of one brilliant thinker working on how to present it better and better for the people of his time over the long course of his teaching career. It makes sense as an integrated whole — self-consistent as a teaching, visible in our practice, an effect of our nature that was present before the Buddha lived all the way up to the present and no doubt long into our future — just as we have it. Valuable as a teaching, for all that. Worth taking the time to understand, starting with trust that what we have of the Buddhas words explains it.

- Eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, etc.

Buddhism counts the five sense organs as we do, plus the mind, which is useful for all the Buddha’s discussions of how we work, though even in his talks we can see that the mind operates differently from the rest. Five senses make contact generated by (usually) physical objects: touch, taste, smell, sight, sound. But the mind makes contact with nebulous ideas.

In its most fundamental sense, this is the division the Buddha is talking about throughout his talks, and in dependent arising in particular, as can be seen in my paper “Anatomy of Quarrels and Disputes”, in which the primary line of thinking covers externals, while the secondary line covers internals. For example, “the dear” (pīya) as both things outside of us that we hold dear, and things inside of us, namely ourselves, that are also dear to us.[↩]

- This is not the only example of definitions of one link including later links. For example — as Bucknell points out — nāmarūpa’s definitions sometimes include phassa (contact) and vedanā (feeling). As far as I can see his theory doesn’t address why that is, but mine covers it easily.[↩]

- On pages 330-331 of Bucknell’s paper, he suggests that nāmarūpa was not a part of the beginnings of the classic formulation of DA, but was an invention added by monastics in their confusion, causing additional confusion. There is no support in the suttas for this.[↩]

- He describes this in SN 12.65 “The City” among other places. [pts S ii 104][↩]

- He also speaks of this sort of inevitability when he discusses karma in detail, for example in MN 136 where he describes what seems to be circular logic about the results of our actions, e.g. sañcetanikaṃ kammaṃ dukkhavedanīyaṃ dukkhaṃ vedayati “intentional action to be felt as painful that is to be felt as painful”.[↩]

- For example SN 35.60 [pts S iv 103] where he suggests we reject the sense organs, their objects, and the awareness (“consciousness”) that arises from them, but I’d suggest that’s a little on the pariyāya (metaphorical) side. In practice I find looking both back and forward to recognize that we’ve been here before, we know where it leads and where it came from, is quite effective at changing behavior.[↩]

- “These observations by WATSUJI, YINSHUN, and REAT indicate that nāma-rūpa, far from signifying ‘mind-and-body’ or something similar, is a collective term for the six types of sense object.” — Bucknell page 325.[↩]

- Bucknell says, “Now, it is an observable fact that, with one partial exception (discussed below), accounts of the branched version present it only in forward sequence.” (p. 330)

It’s true that after the definition of contact, the suttas describe DA moving forward, but clearly that’s because contact is the first moment when there is real action. The Buddha is describing DA from the first moment we can literally see or experience it. But for contact to happen, the drives had to apply their force to make contact happen. So the lesson starts with looking back at what made contact happen, then moving forward to see what happens next.[↩]

- Bucknell does this because the Buddha does effectively say that consciousness arises from those two. What the Buddha is describing there is an even finer-grained view of contact seen through a higher-powered microscope.[↩]

- See “Check Please” below for details.[↩]

- This is what Annie Blanchard’s art at the top of the post, “Tell me about me” illustrates: name-and-form tells consciousness what relevance it perceives the sense object to have to its self, beginning with “good feeling/good for me? bad feeling/bad for me?” and getting more complex as life goes on.[↩]

- The four main volumes containing the Buddha’s talks: DN = Digha Nikaya/Long Discourses. MN = Majjhima Nikaya/Middle-length Discourses. SN = Samyuta Nikaya/Connected Discourses. AN = Anguttara Nikaya/Numbered Discourses. Eye-consciousness is found more frequently than the rest because many suttas shorten the description by just using the first-listed and “…”[↩]

- nāmarūpasamudayā viññāṇasamudayo; nāmarūpanirodhā viññāṇanirodho. These compounds don’t imply tense, so “comes the origination” and “comes the cessation” could as well be represented by “came”.

Bodhi’s translation perhaps gives a better sense of timelessness: “With the arising of name-and-form there is the arising of consciousness. With the cessation of name-and-form there is the cessation of consciousness.”[↩]

- Bucknell admits there is no support in the suttas for any of his theory. He offers one Abhidharmic explanation of DA that combines the looped and “branched” version in a way suggestive of his solution. He posits that the authors had “a residual memory of the branching structure from which it was derived.” It seems far more likely they had the same source material to examine, similar confusion, and so came to similar conclusions as his.[↩]

- See my earlier post to get a view of him trying to make his attempts at patterning clear to his attendant, Ananda.[↩]

- SN 12.65 “The City”. Two suttas later Sariputta includes the looped version — without the “goes no further” portion — as well as the longer standard version with its beginning links, avijjā and saṅkhārā. I see this as a clear indicator that the two versions are completely compatible, since Sariputta knew his stuff.[↩]

- Note that the Buddha here describes aging-and-death as an example of dukkha, not the very definition of dukkha.[↩]

- So not, as Bucknell would have it, “…that the practice of reciting the causal series in reverse order was an innovation, and indeed that this new practice was the immediate cause of the distortions.” We have evidence provided by the Buddha in the suttas that this was the original direction.[↩]

Perhaps I should have added another footnote, with a link to my paper, “Anatomy of Quarrels and Disputes.” Working on looking at that suttas bones gave results that were completely unexpected.

https://jocbs.org/index.php/jocbs/article/view/56