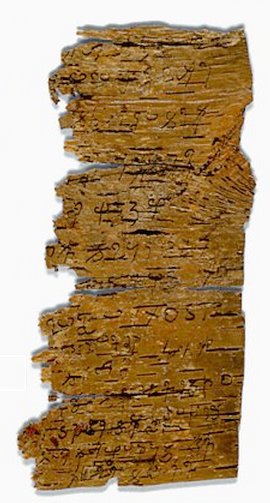

In 1994, the British Library obtained several decaying birch-bark scrolls with writing in an ancient Gandharan script. They contained a variety of Buddhist texts, and were dated back to the middle of the first century — to about the year 50 C.E. Though no one knows exactly where and how they were found, the evidence points to these texts having been buried in clay pots, probably in lieu of throwing them away, after they had been recopied for a library in what is now far eastern Afghanistan, somewhere around the area between Jalalabad and Peshawar, in what was a thriving and cultured area known as Gandhara. The texts are still partly readable, and cover a range of Buddhist works, and include a sutta (AN 4.36) recently discussed, in the post “I Am Not A Man.”

The story as laid out on the Gandharan scrolls is not letter-for-letter the same, or word-for-word, or even phrase-for-phrase. The vocabulary is quite similar, spelling is somewhat modified — and there are small bits missing, as well as the traditional opening lines. The book “Three Gāndhārī Ekottarikāgama-type sūtras: British Library Kharoṣṭhī” has a thorough reconstruction that can be examined through Google Books, but below I offer a somewhat smoothed version that should be enough to let us look at the differences between the readily-available Pali version, and the older Gandharan.

*~*~*

The Bhagavat, traveling between cities, stepped off the road. Seating himself near the root of a tree, he spent the day.

At about the same time a brahmin named Dhona had started out on the same road. Dhona noticed the wheel-marks on the footprints of the Bhagavat on the road before him, thousand-spoked, with all parts complete, sharp, resplendent. Following the footprints of the Bhagavat, he saw him who had traveled on the road. He had stepped off the road and sat near the root of a tree. His appearance was fair, pleasing, his faculties calm, his mind calm, having attained the highest training and calm. . . a protector, trained, controlled, with faculties restrained, like a clear, translucent, serene pond.

Having seen him, he approached the Bhagavat. Having approached, he said this to the Bhagavat.

“Venerable sir, will you be (bhaviśasi) a deva?”

“Brahmin, I will not be (bhaviśe) a deva.”

“Venerable sir, will you be a gandharva?”

“Brahmin, I will not be a gandharva.”

“Venerable sir, will you be a yaksa?”

“Brahmin, I will not be a yaksa.”

“Sir, will you be (bhaviśasi) a human (maṇosu)?”

“Brahmin, I will not be (bhaviśe) a human.”

“Being asked thus, ‘Sir, will you be a deva?’ you say this, ‘Brahmin, I will not be a deva.’ Being asked thus, ‘Sir, will you be a gandharva?’ you say this, ‘Brahman, I will not be a gandharva.’ Being asked thus, ‘Sir, will you be a yaksa?’ you say this, ‘Brahmin, I will not be a yaksa.’ Being asked thus, ‘Sir, will you be a human?’ you say this, ‘Brahman, I will not be a human.’ Who, then, sir, will you be?” (ku re bhu bhaviśasi)

“Brahmin, I am the Awakened One. I am the Awakened One.” (budho mi brahmaṇa budho mi)

*~*~*

The core story is very much the same as the Pali version. The opening lines and the ending of the sutta, however, are quite different. In the later Pali version, Dona begins by wondering aloud whose footprints he is seeing — this is missing from the older version. In Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s translation, the future tense is ignored, so the question Dona asks himself comes out as,

“How amazing! How astounding! These are not the footprints of a human being!”

whereas I would honor the future tense and read it as saying:

“Surely these will not turn out to be the footprints of a human?”

As others (Jayarava in his comments to my older posts, and Woodward in the notes to his translation) have pointed out, the future tense used throughout can be used to capture a sense of wonderment. The phrasing that follows can then be imagined with an Irish lilt to it, asking “Who will you be then? Will you be a deva?” which accurately captures the future tense, while suggesting wonderment about the present. So when the translator assumed — correctly — that the question was *actually* asking about the Buddha’s present state, we can understand why he chose to put it in the present tense though the Pali doesn’t.

The problem is that apparently the question *was* asked in the future tense, and though the Buddha understood, as we do, that it was his current state that was being questioned, he didn’t answer, as one naturally would, in the present tense, acknowledging this. We might imagine a modern conversation to go like this:

Irishman: “Will you be an American, then?”

Aussie: “No, I am not an American.”

The present tense in the answer acknowledges the understanding of the original question.

But the Buddha — in both the Gandharan version and the later Pali — clearly decides to have a little fun with Dona’s wording:

Dona: “Venerable sir, will you be a deva?”

Buddha: “I will not be a deva.”

The Buddha answers in the future tense, and he *means* that he will not, in the future, be a deva — because he knows he will not be reborn in any of the states Dona asks about. He does this for all four questions, and the point is made that he knew all along *exactly* what Dona was asking him, when the frustrated Brahmin points out that each question has been answered in the negative and so he asks, using the same future tense:

Dona: “Who then, sir, will you be?”

and the Buddha answers, this time *not* in the future tense but in the present (showing — using the method of the Irishman and the Aussie, above — that he knew all along that it was his present state that was being questioned):

Buddha: “I am awakened. I am awakened.”

Both versions retain the future tense throughout the body, and change to the present tense only with the very last answer.

*~*~*

Along with a big chunk of explanatory text, the older, Pali version adds a bit of verse at the end that is not part of the Gandhari version:

The fermentations by which I would go to a deva-state

or become a gandhabba in the sky

or go to a yakkha-state & human-state:

Those have been destroyed by me…

The verse, presumably added at a later date since it is missing from the Gandhari, correctly interprets the situation portrayed in the sutta: that the Buddha refers to the state he “would go to” in the future, but will not, because he has awakened. Translating the tenses used in the main body of the story as ‘present tense’, when the original is ‘future tense’, ends up doing violence to the point of the story — which is, for me, as much about the Buddha’s sense of humor as it is about him not being reborn in any state in the future, and his being awakened now.

Even more important to notice is that changing the tense has him saying that he *is* not a man, which people tend to latch onto, to say that what he became post-awakening was some sort of transcendent being. While I do understand the Buddha, in the canon in general, to be saying that he can find no evidence of a self (atta) and has rid himself of what we mistake for the self (anatta), I never see him saying he has become something other than human. Changing the tense distorts what he is saying, on a very important point.

*~*~*

The thing that interests me most about the differences between the older Gandhari version and the newer Pali version are the ways in which the opening got modified (a little) and the ending got added to (a lot), while the body of the story stayed pretty much the same. This tells us a lot about what was deemed most critical to save — unchanged — for the future, even as time went on, and what it seemed was acceptable to do to the suttas. We would not want to change the Buddha’s words (though updating the form the words took to modern equivalents would be okay), nor would we change the heart of the story, but fleshing it out with a little more detail in the opening, or adding a chunk of text to explain why he said what he said would be fine. (We could, alternatively, assume that the Gandharan version had dropped things that the later version retained, but given the extremely repetitive nature of the bulk of Pali texts, and what we know of oral transmission in other cultures, this seems unlikely.)

In the Pali, a large lump of prose got added to the end to explain *why* he “would not be a deva” — detailed explanations about having abandoned the “fermentations” (asavas — aka “taints”) — and this was further reinforced with some verse following the lot.

While I had understood that the Pali texts were modified over time — and that the verses were the most likely candidates for later additions, and so were naturally suspect as “the Buddha’s words” — having the opportunity to see two versions of this remarkable sutta, and compare them, makes a vivid impression about how much faith we should put in the accuracy of the texts, and gives us a little insight into what may be the more reliable portions. The chunks of texts (particularly pericopes — word-for-word repetitions from one sutta to the next) are more likely to have been “dropped in” later, and the parts of the tales that are unique — and at the same time consistent with the Buddha’s core message — can be given a little extra weight as perhaps reflecting actual events.

This is not saying that the pericopes are always wrong — far from it; as in this sutta, it is probably quite accurate that the reason the Buddha will not be a deva, but is awakened, is because he abandoned the taints — but that the sheer weight and number of them in the suttas tends to make us pay more attention to them than to the little nuggets in between, and that may be where the gold is.

Hello Linda (Star),

Luke Rondinaro from the Dianoeidos blog and occasional Darwiniana commenter. …

Good Post. I’m glad to see you’re making these points (“I never see [the Buddha] saying he has become something other than human.”) They go a long way in setting the record straight on what’s important in Buddhism, the problematic character of metaphysical attachments to Buddhist teachings, and so forth.

The problem I have with any of this material, what I’ve gotten out of the Batchelor discussion, and similar lines of conversation is that in spite of its merits, this consideration of Buddhism is banging up against a wall when it comes to either engaging the fuller community of Buddhism enthusiasts let alone the secular community that could really use the insights and principles coming out of this discourse between Buddhism and Modernity.

I know Sam Harris’ opening ventures in creating a rapprochement between secularists and students of spiritual traditions is seen as being unwelcome in many philosophical and religious quarters since he’s supposedly neutering spirituality and mysticism in the process. But what would people rather have? A secular tradition like we seem to have growing now in the West that views all Pre-Modern and non-scientific intellectual approaches to human experience as being absolute nonsense no matter what, or at least having a contemporary secularism that (somehow in and some way) acknowledges Buddhism’s and Taoism’s contributions to the world of developing human inquiry and the oikumene of science with non-scientific modes of human understanding?

I’m afraid that by waving off the Sam Harris types of the world and the Patricia Churchlands, the mystical dogmatists (Buddhist fundamentalists & others) are only shooting themselves in the foot. Modern Psychology and Neuroscience may have their faults, but only by engaging them and the rest of science will these studies ever get past their fixation on reductionism.

Only by being truly engaged by the likes of Buddhism, [Philosophical]Taoism, and world philosophies will these sciences ever truly make their best contributions to human experience and intellectual inquiry yet in the world. That’s the real path to consilience, rather than just having a revived religionism work itself around as the new arbiter of discourse, in place of either science or traditional philosophy.

Anyway, that’s my point after seeing your piece. I’d be interested in getting your views here about what I’ve said and especially about the whole Sam Harris, spirituality and Buddhism, hullabaloo that’s been going on of late on the Web.

Wonderful post. Thanks again for writing it.

Welcome, Luke, and thanks for the thoughtful comment.

My thought is only this: the conversation is best when we allow room for many voices.

I find myself concerned, sometimes, that separating elements of Buddhism out from the well-balanced whole of the teaching will lessen the impact of the various bits — particularly if we try to disguise the origins (“This is meditation, just meditation. It has nothing to do with anything formerly known as a religion.”) — many people seem to have arrived at the wealth of helpful detail that Buddhism provides through one piece or another but if we can no longer recognize the source then the opportunity to find more that’s of use may be lost.

Buddhism does offer more than just stress reduction (I am thinking particularly of Sam Harris’ endorsement of meditation), like a moral system that doesn’t place blame, that fosters tolerance, and a method of insight into the workings of humans in interaction with others that could do a lot to make the world a better place for everyone to live in, if people are allowed to recognize it.

The tension between rejection of religious dogma, and the adoption of a viable system of support seems like a tough one to balance. So the more voices in the conversation, the better.

Fascinating blog, Linda. You and Batchelor make me realize that we need more people scrutinizing the Pali text because it seems like typical Buddhist scholars and monks who study these text are looking through metaphysical glasses based on beliefs they have. They ARE going to miss subtleties that are crucial to the teachings.

I do agree the teaching in it’s entirety has more impact on the individual, but I also think the bits are well worth exploring, even integrating into society without dragging the religiousness of Buddhism into it. Buddhism has some awesome mindfulness techniques that go toward developing a critical mind, a focused mind, and healthier mind.

In recent studies about meditation, while in the beginning studies have shown it’s benefits to stress reduction, they are validating it’s other usefulness too in teaching the brain new habits, dropping old ones, in increasing concentration and focus, in learning. I feel one gets more benefit out of meditation from understanding the Buddhist background right now, but I see that changing as more and more non-Buddhist take up the practice. It will be interesting to see where it leads.

I’m excited that meditation is under scientific scrutiny. But then I do tend to be more of a material girl:-)

Appreciate your study of these ancient text!

Hello Again Linda …

I appreciate your points here about considering the “whole” of Buddhism and in “balancing” the whole of the teaching with its different parts. … Many voices should be part of the conversation to make it a more worthwhile one/Buddhism should be considered in it is fullest possible terms and not in way that merely waters down its tenets.

I agree with what you’re saying here and that’s fine to do. But the challenge, I think, comes when certain bits are argued to be more important that others via a religious reading of the teaching; and when particular voices in the religious community are insistent that they must be proclaimed from the rooftops and enunciated/emphasized as if they were the linchpin of the entire teaching. That makes working from the well-balanced whole a more challenging task.

In the Taoism of Lao Tse, such a dilemma is remedied by differentiating Tao from the 10,000 Things, and by making that formal distinction; realizing that outward form is more or less a useful map for explaining the extrinsic aspect of things, while at their heart is only unnameable Tao, the core of the reality in question.

Therefore, maybe in Buddhism too, we might also apply this kind-of-an-understanding. Maybe the religious ideas of Buddhism are like the needles on a pine tree, essential to the tree as a whole, but no more the core or heart of the tree than its pine cones. Maybe these religious concepts are the literary means by which Buddhism might express its essential principles. I don’t know, but this analogy seems apt to the discussion. What do you think? Can it help shed light on the Buddhist system?

I’d be interested in hearing your take on this question. Thanks again.

Hey Luke. I think you make good points. While reading I was thinking that some people, in looking at Buddhism through the Tao, may see some things (like rebirth) as being of the Tao, and some might say it is one of the 10,000 Things. Or as you put it in the next paragraph, as part of the pine tree, or as pine needles.

I think that all of what the Buddha talked *about* was beyond words, and so everything he said about it was literary means. The theory should be this: that whatever draws people to study the Buddha’s teachings is skillful means. For some people it’s literal rebirth, for some people it’s that concerns about things unseen are not necessary (different strokes for different folks); people drawn to study should eventually get far enough that they see what’s being pointed at for themselves, and no longer need entry-level lessons, whatever paradigm they are couched in. Pine needles everywhere, pine needles falling and crushed under foot. Do we ever get to see the heart of the tree?

“[People] drawn to study should eventually get far enough that they see what’s being pointed at for themselves, and no longer need entry-level lessons, whatever paradigm they are couched in. Pine needles everywhere, pine needles falling and crushed under foot. Do we ever get to see the heart of the tree?”

*********

Good thing to ask! I’ve been thinking about that question too. Do we ever see the ‘heart of the tree?’ For that matter, ‘what exactly is the heart of the tree?’ … It could very well be some sort of naturalistic principle, a dynamic in nature by which all the rest of material forms, energy, and physical things are under-girded. But the more and more I look at the issue, I’m almost being convinced that it’s not a particular thing, force, or physical-natural function in the world. The heart of the “tree” or “reality” or “truth” is not any-thing per se. It’s a principle; and at the core, it could very well be represented by nothing more than an “empty space.”

Strip away the needles and you have the bare bones skeleton of a pine tree. … But we needn’t stop there. In another sense, the bark is another ‘incidental’, not the ‘substance’ or the ‘essentiality’ of the tree, and so that can go too. … Sooner or later, after all this stripping, you literally have nothing left. The ‘heart’ of the tree is in the “whole” of the pine tree; in its totality with all its aspects and parts.

And, yet, even that “whole”, that integrated totality, is not the reality in itself or the pine tree in itself. Strange as it sounds, strange as it seems, the heart of the tree is in its “space.” It’s in that domain between the wholeness of a thing and its nature as being not completely knowable, or nameable, or completely intellectually pegged.

That’s what I see is at the “heart” of the pine tree, and what I think Lao Tse and the Buddha were ultimately driving at (among other things). Mystery, yes! But a special kind of mystery. The one right in front of our noses staring us in the face. … The ‘known world’ stands before us. But do we truly honest-to-goodness ‘know’ it? That’s the question.

[…] we have of the suttas (at this point that is mostly the Theravadan Pali suttas, Chinese agamas, and some very old pieces written on birchbark found in Gandhara), so the ultimate authority on the Buddha of the suttas is the Buddha of the […]